Corollary to Rule Number Three

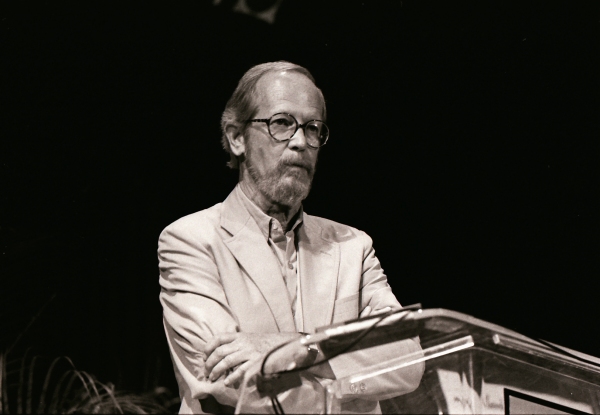

Elmore Leonard died back in August, as you have probably heard. His passing has been characterized as the loss of a national treasure, and based on the five or six books of his I’ve read over the years, that seems like a pretty fair assessment.

Leonard began his career as a writer of pulp westerns, but achieved popular success in crime fiction, where he managed to locate a fertile patch of turf midway between wisecracking romantics in the Raymond Chandler mold and their more spartan hardboiled rivals, and then to cultivate that patch with awe-inspiring consistency. Leonard was funny, but not zany; he was witty, but resisted being clever. He didn’t let his plots push his characters around, and he also had no apparent use for the shadowy psychopathology that fuels the works of his most critically-lauded midcentury peers: nobody in an Elmore Leonard novel is a case study, or a symptom of anything.

Leonard’s great achievement, it seems to me, is his evocation of the idiosyncratic moral universe in which his books always take place; everything else for which he is justly praised—his off-like-a-shot narration, his fleshed-out characters, his ear for dialogue—proceeds from that. The inhabitants of Leonard’s world can never be sure of the consequences of their actions, and they’re too foggy on their own motives to ever settle on a solid code of conduct. What they fall back on instead—if they know what’s good for them, which most of them don’t—is an attitude, or maybe more accurately a stance. Leonard’s heroes understand what they can and can’t get away with, and they know what they look like through other people’s eyes: what they seem to be. Most importantly of all, they know when it’s time to shut up and pay attention. (Leonard’s vaunted dialogue is as much or more a tribute to the value of listening than to the value of talking.) The categorical imperative of this moral universe can be summed up with Leonardesque conciseness in two words borrowed from one of his titles: Be Cool.

Although Leonard’s dialogue is richly excerptable, his adroit treatment of violent action is less so: it’s hard to convey a sense of the slow build to these scenes, and harder still to convey what he cannily omits from them. Nevertheless, I’d like to take a quick look at a few paragraphs from Pronto, the 1993 novel that introduces Deputy U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens, who went on to feature in two more Leonard books and is now the protagonist of the giddily acclaimed FX series Justified. If you’re planning to read Pronto (and I think you should) and you don’t want me to spoil anything for you (as if that were really possible) then please skip on ahead to the Cayucas video below.

The scene from which I’ll quote is set in Liguria, on Italy’s northwest coast; Marshal Givens is there to retrieve an on-the-lam Miami bookie, and has, of course, run afoul of the mob:

Now the fat guy waved his pistol at Nicky, saying, “Come on,” and started toward Raylan again, getting a sincere look on his face as he said, “We want to talk to you, man. Get a little closer, that’s all, so I don’t have to shout.”

“I can hear you,” Raylan said.

The fat guy said, “Listen, it’s okay. I don’t mean real close. Just a little closer, uh? It’s okay?”

Getting within his range, Raylan thought. If he knows what it is. The guy was confident, you could say that for him. Raylan raised his left hand, this time toward the fat guy.

Then lowered it, saying, “I wouldn’t come any closer’n right there. You want to talk, go ahead and talk.”

The fat guy kept coming anyway, saying, “It’s okay, don’t worry about it.”

“You take one more step,” Raylan said, “I’ll shoot you. That’s all I’m gonna say.”

This time the fat guy stopped and grinned, shaking his head, about sixty feet away now. He said, “Listen, I want to tell you something, okay? That you should know.” He took a step. He started to take another one.

And Raylan shot him. Put the 357 Mag on him, fired once, and hit him high in the gut. Raylan glanced at Nicky standing way over on his left, Nicky with his pistol about waist high Raylan put the Mag on the fat guy again, the guy with his hand on his gut now, looking down like he couldn’t believe there was a hole in him before looking at Raylan again, saying something in Italian that had a surprised sound to it. When the guy raised his pistol and had it out in front of him, Raylan shot him again, higher this time, in the chest, and this one put him down.

The sound echoed and faded.

Raylan turned his head.

For characters who are slow to pick up on when to speak, when to listen, and when to make a move, things tend to end poorly in Leonard’s world. Note how Leonard—the master of whip-smart dialogue—sets up the above-excerpted killing with a conversation that’s calculatedly lame. The “confident” fat guy thinks he can smooth-talk his way into an advantage, but he’s not a very good talker: everything he says is vacuous, obviously serving no purpose but to cover his approach. He also thinks this straight-arrow American lawman won’t shoot unless he’s shot at, won’t actually kill over the mere crossing of a line arbitrarily drawn. Maybe we, the readers, think this too.

What’s effective in this scene is its faintly nightmarish quality, both surreal and super-real, as characters who have been playing a game with each other discover too late that they’re using different rules. Like all crime novels, Leonard’s books necessarily depend on violence or the prospect of it for their appeal, and as such they’re open to the charge of being exploitative. Still, for whatever it’s worth, Leonard’s scenes of bloodshed feel true in their circumstances to the way such altercations seem to happen in real life: somebody stubborn encounters somebody stupid, and they both have guns. The situation with Raylan and the fat guy just seems too dumb to actually play out the way it does; we’re not quite ready for what happens.

It’s worth noticing how carefully Leonard lines us up for the slight shock the scene delivers when Raylan shoots; it’s also worth noticing how hard he works to make that care seem like carelessness. Take a look at the description of Raylan raising and lowering his left hand: Leonard separates the two halves of this gesture with not only an ungrammatical period but a full paragraph break between the dependent and independent clauses, producing a queasy slow-motion effect at the level of syntax. (This adventurousness with grammar gets even more pronounced after that first shot is fired, with subordinating elements receding to reflect Raylan’s broadcast attention: good luck diagramming the sentence that includes “. . . Nicky with his pistol about waist high Raylan put the Mag on the fat guy again . . .”)

Significantly, that paragraph break as Raylan moves his left hand also suggests a cinematic shot-reverse-shot. As the hand goes up we’re in Raylan’s head, looking at the fat guy through his eyes; then—period, paragraph—the hand comes down, and we’re looking at Raylan now, from a distance, no longer privy to what he’s thinking. This is critical to achieving the surprise that Leonard is aiming for, a surprise sprung not by revealing but by withholding information: although we’ve just been in Raylan’s head, hearing him assess the fat guy’s confidence and tactics, we weren’t told that he’d made any decisions about whether and when to shoot. Most writers—even, or especially, thriller writers—would prolong this moment like a Sergio Leone shootout, milking it for maximum tension; Leonard knows this, and knows that we know this, and uses our expectations to catch us off balance. (He tips the odds even further in his favor with the phrase “about sixty feet away now”—that adverbial now strongly suggesting that we’ll be receiving additional updates on the fat guy’s diminishing distance from Raylan, when in fact we won’t.)

The thrills of reading most mass-market fiction are pretty much those of watching competitive figure skating: the question is not whether the triple Salchow is coming, but only how adeptly it will be executed. The selection from Pronto provides evidence, as if it were needed, that Leonard is playing a bigger game. What’s most impressive to me is that he makes no attempt to do what virtually all other ambitious crime writers—even really good ones—do to qualify their work as “literary,” i.e. to tack on ornaments like social commentary, mythic allusion, and/or poetic language. (After all, as Elisa Gabbert has demonstrated, even contemporary open-form poetry has its own set of stock jumps.) Leonard’s art, by contrast, is subtractive, paring away received techniques and—as we saw above—even basic coordinating elements when it suits his narrative purposes. The combined effect of all his small omissions, misdirections, and discombobulations is to induce us to grab hold of the figurative armrests, as if we’ve come to suspect that our driver might be a little drunker than we thought: we’re now wondering whether this guy really knows what he’s doing. Leonard’s seemingly cavalier departure from the standard slow build of pulp-fiction syntax demonstrates that this book’s narration will not be leading us by the hand through the remainder of the tale. And that realization, naturally, will increase our suspense as we close in on the ending, since our efforts to guess what’s going to happen are now complicated by our efforts to figure out what kind of a book we’re reading, and whether it gives a particular damn about delivering the conventional pleasures of a crime thriller. When those conventional pleasures are indeed served up a few dozen pages later, it feels less like the clicking of formulaic genre gears than like a fortuitous accident, like things might not have worked so cleanly out after all. That’s pretty much how Leonard does his thing: staying a step ahead of our expectations, managing our attention from moment to moment, and doing so with enough humility to disguise his best and smartest narrative moves as sloppiness or whimsy.

I’d been thinking about Leonard a lot over the summer, even before he died. To be more specific, I’d been thinking about the famous and widely-quoted “Writers on Writing” feature that he contributed to the New York Times back in July of 2001, a piece that has come to be known universally among people inclined to compile, argue about, and obsess over putative “rules for writing”—of whom I am one—as Elmore Leonard’s Rules for Writing:

These are rules I’ve picked up along the way to help me remain invisible when I’m writing a book, to help me show rather than tell what’s taking place in the story. If you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after, and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over.

The most famous of the rules is probably Number Ten: Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip—and understandably so, since many rightly detect in this rule a shift of responsibility from reader to writer that vindicates certain resentments lingering from high school English class—but personally I find it a little too glib to be useful. The Leonard rule that I hear quoted most often by actual writer-type-people is the pleasingly cut-and-dried Number Three: Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue. It’s pretty great advice: once you start paying attention to dialogue tags, I promise that you will find violations of this rule to be among the surest indications that Amateur Hour is underway.

But I would also argue that the near-gospel status achieved by this rule comes with a small downside, that being an overemphasis on the lexicon of dialogue tags at the expense of consideration of their placement, which is where competent writers of narrative can really show off their ninja skills. Obviously the main purpose of dialogue tags is to inform us who’s speaking, and (when absolutely necessary) to help us situate the speaker in the scene, but that’s not all they’ll do for us. A dialogue tag can also function as a non-grammatical pause—a beat—that captures the rhythm of speech in a way that punctuation simply can’t. In the example from Pronto above, when Raylan says, “You take one more step, I’ll shoot you,” something happens at that comma that the comma by itself can’t convey: a squaring-off, a slight intake of breath that indicates that shit just got serious. Although we don’t know it yet, this comma marks the determinate moment in the scene, the one that seals the fat guy’s fate, and maybe Raylan’s too. The subtlety of the moment can’t really be rendered through the diffuseness of an ellipsis, or by the dramatic wait-for-it fermata of an em-dash. Something else is needed. Thus:

“You take one more step,” Raylan said, “I’ll shoot you.”

This placement-of-dialogue-tag trick does not, of course, qualify as a major discovery on my part, and is hardly unique to Leonard: any writer who knows what she or he is doing uses it from time to time. It’s the sort of technique that’s particularly indispensable to comic writers who need to slow down their punchlines; I first became conscious of the practice during my otherwise entirely clueless adolescence, when I noticed Douglas Adams doing it in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy . . . although in Adams’ case it can get a little out of hand, verging on shrug-shouldered self-parody:

Ford looked at him severely.

“And no sneaky knocking down Mr. Dent’s house while he’s away, all right?” he said.

“The mere thought,” growled Mr. Prosser, “hadn’t even begun to speculate,” he continued, settling himself back, “about the merest possibility of crossing my mind.”

(Re “severely,” “growled,” and “continued,” q.v. Leonard’s Rules Three and Four.)

And yet dialogue tag placement is still not exactly what I was thinking about over the summer. What I was thinking about, broadly speaking, is another basic but underappreciated function of dialogue tags: to reveal not only WHO is speaking but THAT someone is speaking at all. In conventional narrative writing this isn’t such a big deal, since quotation marks signal that we’re in dialogue, but in certain unusual narrative situations—in unconventional writing that omits quotation marks, for instance, or in narratives that are encountered aloud rather than on the page—the writer has to adopt other strategies to make it clear when we have entered reported speech.

Unless, of course, the writer doesn’t WANT it to be clear. What I was thinking about this summer, narrowly speaking, was the song “High School Lover” by the band Cayucas (which in a recording-studio context pretty much just means singer-songwriter Zach Yudin). The song appears on their debut album Bigfoot, as well as, I gather, in, like, a Verizon commercial or whatever.

Speaking yet more narrowly still, I’ve been thinking about the song’s first thirty-odd seconds. The reverbed hey (or is it more of an eh?) that cancels the crowd noise and kicks things off registers mostly as a canonical rock ’n’ roll hype move, but there’s also something ambiguous in its tone—a little glum, a little peevish—that positions Yudin’s opening salvo somewhere between let’s-get-this-party-started! and somebody-stole-my-bike! The music it ushers in doesn’t exactly resolve the ambiguity: the boing-boing bassline sets out jauntily enough, but then retreats at its midpoint to an anxious whole tone (I think) from where it began before scrambling to complete its loop. Still, the slap-happy percussion that pushes everything along seems to indicate that this will be a fun track for the kids to mash-potato to . . . maybe when Yudin drops some lyrics we’ll know for sure which direction he’s headed. Ah, here’s we go:

Are you going to the party on Saturday?

Hell yeah! Mystery solved! It’s beach blanket bingo time! Oh, wait:

she asked. I said I didn’t know.

See ever since I saw you on the back of some guy’s bicycle

well I’ve been feeling kind of so-so.

See what I mean about the dialogue tag placement? Rather than making us feel the loneliness and resentment of the narrator as he avoids the party and walks around it and thinks about it all night long, the music and the first line contrive to put us AT the party that he’s skipping before we even realize he’s skipped it, which locates us at a peculiar critical distance from him: maybe a little guilty at his ostensible exclusion from our pop pleasure, and also a little unmoved by and skeptical of his apparent sullenness—if only because, c’mon, man, that is clearly not what this song is about. This critical disconnect is key to the somewhat subtle game that Yudin is playing.

You think I’m overthinking this? My friends, I have not even begun to overthink this. Because, check it out, after a first verse and a chorus that spell out the wronged narrator’s frustrations with the object of his unrequited affection, Yudin does it to us again:

Did you get the letters that I sent last summer?

you asked again and again.

Well they’ve piling up on the top shelf in my closet

and I read them every now and then.

Wait, what? When we reach the beginning of this second verse, everything we’ve heard so far has led us to believe that this is still our lovelorn narrator speaking, having spent his sorry summer trudging back and forth to an empty mailbox . . . but nope: we’re being quoted to again. It is in fact our feckless hero who has been receiving these letters—letters he still hasn’t acknowledged (“again and again,” she asked!)—and now he’s the one who’s sulking because this girl caught a lift on some other dude’s bike?! You’re not exactly proving your case here, cowpoke.

But let us consider the milieu of “High School Lover,” which is, of course, suburban adolescence (the narrator’s rival’s default means of transport being our tipoff). And this, of course, is exactly what suburban adolescence was like: a maddening sequence of shared attractions that somehow never amounted to anything, a chaotic and dispiriting jumble of hoped-for rendezvous thwarted by awkwardness, cowardice, confusion, and a persistent revulsion at the plain prospect of growing up. (Okay, that’s what suburban adolescence was like for ME. If you are the sort of person who spends a typical evening celebrating your latest eight-figure real estate deal by speeding down empty freeways in your Audi coupe with the stroboscopic pulse of high-mast streetlights lashing your coke-blown pupils instead of hanging out in your jammies reading cultural criticism on the internet, then your experience may have been different than mine, and I honor that.) What Yudin is attempting in this seemingly breezy summertime top-down pop song is an oblique investigation of the inexhaustible mystery of early adulthood, a mystery best summarized with the timeless question what was I thinking?

Toward this end, the song’s dialogue-tag confusion has one more trick to play, and this time it’s an ambiguity that isn’t—and can’t be—completely resolved:

It’s got me feeling kind of stuck, like what the fuck is going on,

someone tell me what is happening.

Yeah you’ve been acting like you’re too cool for far too long.

It’s okay, it’s just kind of embarrassing.

So . . . is this reported speech, or not? Is this the narrator taking the girl (Elizabeth) to task for her alleged fickleness? Or maybe imagining himself doing so, hours or days or years after her seemingly innocent query about his Saturday plans? Or is this Elizabeth talking, trying to figure out what specific as-yet-undiagnosed psychological malady might lead the narrator to ignore an entire summer’s worth of envelopes inventively collaged with clippings from Sassy? The text (ha! I just called some indie rock lyrics “the text”!) will support any and all of these interpretations. We have now passed the song’s point of laminar-turbulent transition, beyond which complete understanding—not only between the two mixed-up teens, but also between the narrator and us, the real audience for his complaint—has become impossible.

(If we seek clarification on this point from an external authority, we encounter yet more evidence of subterfuge. I had a brainstorm that checking the printed lyrics on the CD case—y’all remember CD players, right? Laser Victrolas, we used to call them?—might clear things up, and lo and behold and sure enough, the telltale punctuation is indeed present:

Are you going to the party on Saturday? / She asked, I said “I didn’t know . . .”

Got that? Those quotation marks are the only ones that appear in the printed lyrics to “High School Lover,” and they—just to be clear—CANNOT BE CORRECT. Although, as I have just argued, there are a couple of ways that quotes might plausibly be deployed in these lyrics, this ain’t one of ’em. Try it: Are you going to the party on Saturday? “I didn’t know.” Um . . . you didn’t know WHAT? And how is that an answer to my question?)

What is being dramatized in “High School Lover” is a progressive breakdown of language. Yet this is not some gnarly poststructuralist aporia that Yudin has sprung on us to expose hitherto unsuspected glitches in the linguistic system: language itself is not the problem. Rather, this collapse proceeds directly from a shortcoming in the narrator’s character, specifically his inability or unwillingness to communicate in words, to enter the semantic realm in any kind of committed way. This deficiency manifests most clearly in his failure to respond to Elizabeth’s letters, but also in the evasive lameness of the few rote utterances he does seem to manage, from his overloaded response to her opening question (I didn’t know not being equal to I hadn’t decided), to his characterization of his jealousy and wounded bafflement as “feeling kind of so-so,” to his insistence—really an admission—that he’s been “saying the things [he] thought [he] should.” The song’s various narrative muddles—its lack of clarity about who’s speaking to whom when, about whether actions and utterances are real or fantasized, etc.—are obviously also symptomatic of the problem.

But the song does evoke one moment when the narrator manages to speak up, to put aside his paralyzing concerns about coolness (and lacks and surfeits of it), to put himself at risk, and to say, for better or worse, what is on his mind: a moment when his “words came out one after another.” This is the moment—hard to situate precisely on the song’s timeline, but let’s figure it happens early, prior to the summer of piled-up letters—when he opens a door to the sight of Elizabeth undressing. Given that the incident shocks the narrator, like some reverse Actaeon, into unguarded speech, I think we can assume that it comes about by accident. We should note too that this scene is described in the chorus, i.e. in the part that repeats. (Okay, just once—it’s a short song—but still.) Even as words fail, the song’s structure tells us something the narrator can’t articulate and may not even understand: that this oops-forgot-to-knock episode is the key moment in the story, a memory that our mixed-up hero can’t get

rid of or get past. What he really needs, whether he knows it or not, is to somehow regain access to the shared vulnerability of this unplanned encounter, this instant of grace and peril, this missed chance to connect and be transformed.

That classical reference in the previous paragraph was not entirely gratuitous, I’m afraid. I have asserted elsewhere that myth, being the opposite of history, readily lends itself to depicting the suburban experience; it is also an easy medium for the dramatic and disempowered confusions of youth, for approximately the same reasons. In Ovid’s version of the Actaeon tale—not the original, but it might as well be, cf. Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You”—the hunter spies the goddess Diana nude at her bath, a turn of events with which she is SO not cool; she turns him into a stag, and he gets killed by his own hounds. What’s interesting is that Ovid’s telling places less emphasis on Actaeon’s physical transformation than on the detail that Diana also renders him mute. (Not the most intuitive choice of punishment for a voyeur: when Tiresias, for instance and by contrast, stumbles upon the nude Athena, she blinds him.) “Go tell it, if your tongue can tell the tale,” Diana mocks (in the dogged blank verse of Brookes More’s translation), “your bold eyes saw me stripped of all my robes”—and sure enough, when the now-quadrupedal-and-antlered Actaeon tries to convince his ravening pooches to chill out for a second, he cannot speak to identify himself. The hunter . . . has become the hunted. Cue Twilight Zone theme.

Now, to be sure, Elizabeth is no goddess—she’s just another awkward teen—and at the sight of her nakedness our narrator is rendered a blabbermouth rather than struck dumb. (Notably, he never fesses up to what he says on this occasion.) But despite these differences, there remains a key correspondence between “High School Lover” and Ovid’s Actaeon story, in that both are built on the same conceptual armature: a right-angled axis of speech and sight. Our narrator may be uncomfortable using language, but he is very damn comfortable being a spectator, and he makes persistent efforts to keep his interactions with Elizabeth as optical as possible. His explanation of his noncommittal response to her opening question, for instance—if it’s actually articulated at all, which seems doubtful—employs the same verb twice in quick succession (“See ever since I saw you”); he then goes on to impugn the “look” in Elizabeth’s eyes, and to characterize the narrative circumstances as a “movie” that he’s been (passively) watching.

But the ultimate indictment of his retreat away from telling and toward looking arrives at the end of the second verse, in a cryptic final scene that isn’t much more than an image:

See I’ve been sneakin’ I’ve been sneakin’ I’ve been sneakin’

wondering just what I’ll see.

You turned around and stared, you squinted then you glared,

and I was leaning back in the passenger seat.

What to make of this? Well, as an interpretive palate-cleanser, let’s figure that the switch from the bicycle of the first verse to the automobile of the second suggests a passage of time, the approach of adulthood, and the waning of what once might have passed for innocence. Furthermore, the narrator’s location in the passenger seat indicates a persisting lack of agency and responsibility. Cool? Now let’s cut to the freakin’ chase: check out that semi-amazing sequence of looking verbs—the visual equivalent of dialogue tags—that describe what Elizabeth is doing in this scene. Stared! Squinted! Glared! Sounds like she’s none too happy with our guy. But if the principal aim of his passive-aggressive efforts has been to keep things, y’know, purely ocular between him and this chick, then it seems he has succeeded abundantly.

Because what’s actually happening here? Could it be that the narrator has talked one of his car-equipped sleazeball buddies into idling in front of Elizabeth’s house while he ogles her through the blinds, hoping for a deliberate repeat of his earlier fortuitous peepshow, only this time without any attendant obligation to account for himself: a purely retinal one-way encounter in which he risks nothing and holds all the cards? And could it be that bright-eyed Elizabeth has just gotten wise to their creepy stakeout, rushing indignantly to the window, leading him to hunker out of sight? You think?

Even if you don’t totally buy that scenario, I think it’s safe to say based on available evidence that this a song about a guy who won’t talk to a girl—even though he digs her, even though she clearly digs him—because he’d rather just look at her. Dyed-in-the-wool putz though this kid may be, the song leaves us enough room to grant him a small measure of sympathy: although his position is clearly more privileged than Elizabeth’s, he and she are both snared in the same set of social codes, codes that regulate his role as a spectator as assiduously as hers as an object on display, thereby making it just about impossible for them to encounter each other on equal footing. In a sense this social system—invisible, internalized, all-pervasive—gets the first and last word, evoked by the crowd noise that we hear under the beginning and the end of the track.

Anyway, that is some—some—of what I think is going on in “High School Lover.” And it’s not even my favorite song on the album.

During his brief time in the pop sphere—first with his solo project Oregon Bike Trails, and now with Cayucas—it’s safe to say that Zach Yudin has not exactly emerged as a critics’ darling. In reviewing Bigfoot for Pitchfork (and let’s face it, Pitchfork remains the indie rock equivalent of Standard & Poor’s) Ian Cohen awarded it the eyebrow-elevating score of 4.9 out of a possible 10, the sort of grade one might receive on an undergrad survey-course pop quiz for simply bothering to show up. Cohen’s major knock against Bigfoot seems to be that it’s derivative of the first Vampire Weekend album, an assessment that would probably be more damning if Bigfoot were obviously the inferior product. I don’t think that’s obvious at all.

I mean, sure, Cohen’s not wrong: Yudin’s work IS derivative—of Vampire Weekend, of Beck, of the Beach Boys . . . hell, I think I’m hearing some Cure in there too, and maybe some Belle & Sebastian, and who knows who else. But I’m afraid that if I make the pretty-much-self-evident point that Vampire Weekend is no less derivative—they seem to be doing their level best to approximate Matador-era Spoon playing Congolese soukous on a Wes Anderson soundtrack, and I say that with total admiration—then I will only succeed in reinforcing Cohen’s suggestion that being derivative is a bad thing, res ipsa loquitur, when in fact it’s one of the core strategies by which contemporary pop music connects with its audience, and has been so for quite some time, at least since the dawn of the hip-hop era. It seems like we ought to be past arguing about whether or not this pop intertextuality is legitimate: when musicians are able to engage the full depth and breadth of their iTunes-account-holding audiences’ musical lexicons, our default assumption should be that they will avail themselves of this option, not that they won’t. Back in the early 90s, a few rock and pop artists were buoyed to cultural prominence by their hip-hop-inspired facility with a vast range of styles and genres; these days such working methods are so run-of-the-mill as to barely merit comment. Observing that Yudin’s music is heavily referential to other music is about one degree of perceptiveness beyond just recognizing that the stereo is on; I’m not awarding any points for that. Am I out of line in expecting professional music critics to consider what a work is doing with its appropriations, instead of just consigning it to a twig on some imagined indie-pop version of the phylogenetic Tree of Life?

Cohen’s closing verdict on Bigfoot (or maybe on Yudin; the grammar seems a little deadline-damaged) is as follows: “observant, but lacks insight, descriptive without offering any commentary, nostalgic without feeling the pain from an old wound. [Pitchfork’s link—and seriously, Ian, I know you’re not writing this for, like, your dissertation committee or whatever, but is that really the best you could do?]” A few months after Pitchfork issued its thumbs-down of record, Paste ran a cover story on Cayucas that reads suspiciously like an awkward sidelong rebuttal of Cohen’s review; the author, Ryan Bort, pretty much argues that Bigfoot ought to be valued as a collection of catchy, simple, sentimental songs, and not faulted for its failure to blaze new trails, because, good lord, does everything have to be Metal Machine Music? It does not! According to Bort, Yudin . . .

. . . doesn’t approach his topics obliquely, instead simply remembering the nostalgic event he’s addressing and listing his associations, those things from that past that stick in your mind as mental totems of more innocent and blissful times. A certain kind of car, a girl on the back of a bicycle, that true-to-scale Michael Jordan poster on a wall—it all transports listeners to another time and place, and because of how friendly Yudin’s voice is, it’s hard not to feel good about all that’s past—even if regret is involved.

Bort’s take on Cayucas, I’m sorry to say, misses the mark even worse than Cohen’s does. The most cursory listen to “High School Lover” makes it clear that the girl on the back of the bike is no “mental totem” triggering bittersweet bliss, but instead a spur to contemplation and reassessment: very precisely the “pain of an old wound” that Cohen (through the expedient and imprecise filter of Don Draper) bemoans the supposed lack of. Oh, and that Michael Jordan poster? Damn glad you brought that up, Ryan, because it, on the other hand, is a perfect example of what Yudin is up to—just not for the reasons you’re arguing.

The lyric in question, which appears in the song “Will ‘The Thrill,’” is actually “Look at the posters that are on the wall / Michael Jordan standing six feet tall.” Live and in person, of course, Michael Jordan is six foot six; in other words, the poster is big, but it’s not “true-to-scale.” This is a detail that we’re meant to catch, and to think about. The song is probably dead-on accurate about the size of the poster; the poster is not accurate about the size of Michael Jordan. This is something that, say, a seven-year-old boy is unlikely to notice when that poster first goes up, but something that, say, a seventeen-year-old boy will notice when he’s wondering whether it’s finally time to take it down. The image evokes nostalgia, sure, but also a twinge of resentment at the countless small frauds perpetrated on us before we’re old enough to notice; it prompts a consideration of how our perceptions are embodied, and how our perceiving bodies change over time. I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to say that it also provides an opportunity to think about the ways that gender in general and masculinity in particular are learned, rehearsed, and performed. (Similar gender-tweaking case in point: the California beach town that provided the band’s name is Cayucos, not Cayucas.)

But the best thing about the Michael Jordan poster line—the thing that makes it effective, and makes it representative of Yudin’s whole project—is that its subtle and complex resonances seem to have been evoked entirely by accident. In fact, these errors-that-aren’t-errors are all over Yudin’s songs, and their very ubiquity is the best clue that there is method in his apparent carelessness. Take, for instance, the late-placement-of-dialogue-tags trick that I described above: the resultant confusion about who’s speaking comes off as merely sloppy until Yudin pulls it a second time. There’s another, similar fakeout sixteen bars into the first verse of “High School Lover,” at the exact point where a half-century of pop-song convention leads us to expect the chorus to drop; Yudin knows this, and he knows that we know this, and he reinforces our expectation by placing the lyric “there was gonna be an ending”—which, thanks to the rhyme scheme, we can totally see coming—just prior to where we think there’s, y’know, gonna be an ending . . . and then he keeps the verse going for eight more bars.

For us listeners, this creates a tension akin to the sense that our cabbie has just driven past our exit . . . but tension, needless to say, is exactly what a songwriter wants leading up to the big release in the chorus, and delay and deferral are the classic means of achieving it. (Clive “Kool Herc” Campbell’s famous realization that a DJ can extend a track’s instrumental break by switching back and forth between two turntables spinning two copies of the same record, thereby driving a dance floor insane—a discovery that pretty much gave birth to hip-hop, and by extension much of the past 35 years of popular culture—is only the most obvious example of this method.) But here again Yudin’s trick isn’t to make the technique seem new, only to make it seem unintentional, which it most certainly is not. The lyric that immediately follows “gonna be an ending”—“to the story to the story to the story”—is a shift into neutral, a sputtering pause that lets us realize what’s just happened: the approximate equivalent of a cartoon coyote running in place in midair, its plunge into the chasm unaccountably interrupted. At first the repetition seems lazy, like a dummy lyric left in place, which reinforces Yudin’s feigned ineptitude; only when he does it again at the same spot in the second verse (“I’ve been sneakin’ I’ve been sneakin’ I’ve been sneakin’) does the finer grain of the song’s structure become apparent.

Yudin seems to have a real fondness for repetitions like this: lyrics that give the initial impression of being redundant, or slack, or gauche. Elsewhere on Bigfoot we find instances of shining sunshine, piled-up piles, and hidden-in hiding places (reiteration-with-grammatical-shift evidently being a Cayucas stock-in-trade) and these serve to advance Yudin’s purposes in a couple of ways. First, they seem stupid but sound great, particularly when braided into the already dense weave of assonance, consonance, and internal rhyme in the typical Cayucas lyric. Second, they signal something important about the scope of the project: about what it is and isn’t trying to accomplish, and how it does and doesn’t hope to engage its audience. Stating repeatedly that things are equal to themselves is a way of indicating that Cayucas has no particular thesis to advance, no case to prove, no real desire to impress us with cleverness or insight. The songs are playful, and thoughtful, but they’re not written in code; they contain depths and subtleties, but they don’t withhold them and don’t depend on them. The listener doesn’t have to resort to analysis to intuit that they’re there.

In other words, Yudin’s songs are pop in the most basic sense: they welcome all comers while privileging none, evincing an aw-shucks modesty that I am inclined to ascribe—perhaps counterintuitively, but think about it for a second—to absolute confidence and clarity of purpose. They take pains to lay no claim on any occult subcultural authority, but instead do business in an egalitarian zone where music is primarily a manifestation of musicians’ own fandom, and the barrier between band and audience is permeable to the point of impalpability: a precarious midrange sweet-spot that is, as Yudin’s own lyrics put it, “beautiful / somewhere in between dumb and kind of cool.”

Part of the deal with this egalitarian approach is that Yudin has to be really overt in citing his influences, lest they become Easter eggs for sophisticates: checkpoints instead of welcome signs, occasions for demonstrating that some listeners “get it” while others don’t. With (for example) Yudin singing from the low end of his pitch range in the persona of a puerile and delusional would-be lothario, “High School Lover” sounds a hell of a lot like a Beck song . . . which is why Yudin pretty much lifts the chorus melody from “The New Pollution” for his own song’s coda, a not-admitting-but-insisting gesture which makes the lineage impossible to miss and snatches canny comparisons from would-be critics’ throats. The opening song on Bigfoot (“Cayucos”) evokes the janglier end of the 1980s new wave pool . . . which I’m guessing is why it contains both the lyric “c-c-c-c-chameleon” AND some late-in-the-game guitar that very strongly recalls the main riff from “Just Like Heaven.” And so forth.

As Cohen’s piece indicates, Yudin’s just-own-it strategy for hipster-proofing his influences—which depends on his reviewers to grasp the obvious and then refrain from pointing it out—has not been 100% successful. Nevertheless, on this point I’m inclined to allocate Cayucas more sympathy than blame, especially since Yudin seems motivated by generosity toward critics and regular listeners alike . . . to the extent that there’s a difference these days. Okay, I promise I’ll lay off this soon, but the layers of complex half-assedness in this Pitchfork review are still blowing my mind: Cohen complains that “Ayawa ’Kya,” Bigfoot’s penultimate track, “sports the kind of onomatopoetic fake patois that people who hate Vampire Weekend assume they use in all of their songs.” But, um, dude, if Cayucas is—as you’ve just argued—worshipfully imitative of Vampire Weekend, shouldn’t we figure that Yudin knows they don’t use fake patois in all of their songs? And that “Ayawa ’Kya” might therefore be better understood as an affectionate parody of, let’s say, “Cape Cod Kwassa-Kwassa”—a parody pointedly written from outside the moneyed East Coast milieu that Ezra Koenig and his bandmates position themselves within, as indicated by the last intelligible line of Yudin’s song, “feel like I feel like I feel like I feel like I’m so poor”? Maybe? (Also, that’s not what onomatopoetic means. Glossolalic? Whatever.)

Anyway, my point here, basically, is this: there are smarter songwriters than Zach Yudin in the world, and there are less pretentious songwriters than Zach Yudin, too, but I think you would have a hard time filling up a city bus with songwriters who are both smarter and less pretentious. I think this is something that’s worthy of praise, and I’d like to see Yudin get more of it . . . or, at minimum, a closer examination than he seems to have received to date.

I’ve been giving the paid critics at Pitchfork and Paste a hard time—which I think they’ve earned—but I confess I’m not unsympathetic to the difficulty of their task: Bigfoot is a tough album to write a solid 700-(as opposed to 7,000-)word review of, if only because Yudin throws so few pitches into critics’ strike zones. In fact, Yudin’s not throwing much of anything anywhere. Toward the end of his review, Cohen—as if suddenly worried that he’s missed a stitch—accuses Yudin of “failing to recognize the difference between leaving something to the imagination and making the listener do all the hard work,” a charge which fails to acknowledge that these are not a songwriter’s only two options for engaging an audience. Yudin doesn’t neglect to “offer commentary” on the milieus and circumstances evoked in his songs; he purposefully avoids it. Rather than doing what virtually every other post-Johnny-Rotten indie-rock frontman does—i.e. asserting his status as a subcultural authority, a personality with something to say—Yudin has taken on a trickier mission, at once more modest and more ambitious: creating conditions for his listeners under which they can see the world through his eyes, consider the things he considers, and feel as if they got there entirely on their own. To work in one final sports reference that I have no real qualifications to employ, Yudin operates like the proverbial no-stats all-star: it’s sometimes hard to say exactly what he’s doing, but remarkable things seem to happen in his presence with surprising consistency.

And this, at long last, brings me back to Elmore Leonard, whom I obviously understand to be linked to Zach Yudin by more than the adroit use of dialogue tags. Leonard characterizes his famous tips for writing as “rules I’ve picked up along the way to help me remain invisible;” by way of explanation, he adds: “If I write in scenes and always from the point of view of a particular character—the one whose view best brings the scene to life—I’m able to concentrate on the voices of the characters telling you who they are and how they feel about what they see and what’s going on, and I’m nowhere in sight.” That’s pretty standard show-don’t-tell writing-workshop fare up until that last clause . . . but that final step of killing your darlings, brushing over your own footprints, and vanishing behind the text is a doozy, and one that’s rare to see anybody even try to pull off successfully. (I used to think I’d spend a lot more time here analyzing variations on this approach to making art, which is why this blog is called what it’s called.)

A great many young writers pound out tens of thousands of words in the hope of cultivating an ephemeral quality often called “voice”—which near as I can figure refers to an engaging combination of style, substance, and sensibility—with the understanding that this quality is what will win them access to the iron-clad gates of the cultural apparatus, where this “voice” might one day, with the proper promotional nourishment, be cultivated into a brand. Leonard’s advice points the way down a vastly longer path, one that eschews pyrotechnic stagecraft in favor of a quieter and more measured approach that exerts a plausible claim on real magic—real because it occurs not on the page but in the minds of the audience, one at a time. (Leonard’s eleventh rule that sums up the previous ten: “If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”) It’s always been rare to see artists who have the poise and humility to work this way, and it seems rarer all the time—maybe because the cultural apparatus just doesn’t grant them admittance anymore.

I guess we’ll see. Props to Zach Yudin for giving it a shot.

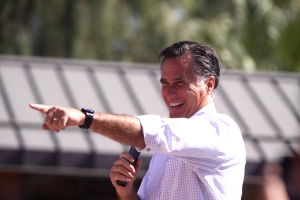

Romney’s douchebag problem

One of the major obstacles that Mitt Romney faces in his campaign for the presidency is the fact that a great number of Americans regard him as a total douchebag.

Why is this so? When we call somebody a douchebag, what do we mean?

Let’s begin with an informal connotative survey of the term. The dutiful aggregators over at Dictionary.com cite the 2009 Collins English Dictionary and the 2012 Random House Dictionary as respectively providing “a contemptible person” and “a contemptible or despicable person” as definitions. For our purposes, these clearly will not do. They make “douchebag” out to be synonymous with virtually every other insult, which simply cannot be the case: a pejorative like “douchebag” derives half its force from specificity, from the sense that its punch has landed right where it hurts. (The other half, needless to say, is from the standard shock value that all profanity manages through the impassioned disruption of civil discourse.)

It’s safe to say that “douchebag” has been long unmoored from its literal referent—i.e. the reservoir of a semi-intrusive and dubiously effective personal hygiene device. A little monkeying around with date ranges in Google Book Search indicates that the word has been employed metaphorically as a slur since at least the 1930s, with appearances in print no doubt lagging far behind conversational usage. “Douchebag” seems to have been a beneficiary of the great American linguistic flowering that followed World War II: one among innumerable expressions extracted from their regional and socioeconomic origins, cross-pollinated in various barracks, and redistributed through the demobilized nation like dandelion seed.

Its meaning has retained a tendency to drift. Dictionary.com also gives us an entry from the Dictionary of American Slang and Colloquial Expressions—fourth edition, copyright 2007, and yes, this is indeed an instance of a website referring us to a five-year-old printed reference book on the subject of contemporary slang, which strikes me as about as desperate and pathetic as a cat trying to get a Post-It off the top of its head—which defines “douche bag” as 1) “a wretched and disgusting person,” and 2) “an ugly girl or woman,” definitions that I suspect went untouched in that 2007 revision. Early uses of the insult do indeed refer to ugly and/or undesirable females—I’ve found suggestions that the phrase “old bag” may be a derivation—and this is kind of interesting, since nowadays we hear the pejorative applied pretty much exclusively to dudes. (Perhaps not surprisingly, it seems to have been borne across the gender divide on the backs of gay men; Henry Miller’s Rosy Crucifixion novels, for instance, published between 1949 and 1959, contain passing references to a drag performer called Minnie Douchebag.)

In the early 1980s “douchebag” really blew up, tipping into broad use among middle-class male teens. Although its application seems to have been fairly indiscriminate, by this point it had pretty much settled on male targets. In keeping with my earlier assertion—i.e. that innovation in profanity, pre-cable and pre-internet, was mostly driven by armed conflict—I’m going to suggest that the groundwork for the sudden rise of “douchebag” was really laid by the U.S. military, which found itself obliged to conscript a bunch of relatively educated, relatively affluent young men and send them off to a highly suspect shooting war in Southeast Asia, and to do so in the midst of a sweeping and convulsive transformation of American culture. Dealt this exceedingly crappy hand, a generation of frustrated drill sergeants had to come up with a rhetoric and a lexicon that would define the harsh, hierarchical, dangerous-as-hell masculine space inhabited by the combat serviceman against the polymorphously perverse rock-’n-roll carnival then going on in the civilian world to the advantage of the former. Most people, it seems, would rather have sex and go to rock festivals than get shot at; unable to appeal plausibly to patriotism, or to a devil-may-care sense of adventure, military rhetoric set out instead to denigrate the youth culture—and the recruits plucked from it—as inane, ignominious, abject, feminized, and feckless. Thus: douchebag.

With these preconditions established, the accomplishment of what I’ll call the First Great Douchebag Breakthrough was a matter of relative ease, somewhat akin to a successful volleyball return: the “set,” in this instance, almost certainly occurred on May 24, 1980, with the final episode of the fifth season of Saturday Night Live—the last one performed by the original cast—and a skit entitled “Lord Douchebag.” Although the skit relied more on the literal meaning of the word than on the connotations it had accrued during the Vietnam era, it made “douchebag” widely available to the late-night-TV-watching public: to an unprecedented extent, it put it into play. The fact that many young male viewers had no idea what the word meant or why it got such a big laugh made SNL’s use of it even more culturally potent, a seeming paradox we witness again two years later, when the “spike” came along.

If, hypothetically, you are an adolescent or preadolescent boy, and you see a movie in which a kid calls another kid a name, and that name is a word that’s unfamiliar to you, and the movie kid’s use of it draws an immediate reaction (shocked) and reproach (mild) from a movie adult, then you are damn sure going to remember that word. And once you figure out that although the word is clearly impolite, it’s not really a bad word—you can say it on TV—then you are going to start using that word a lot. We can therefore date the real watershed moment for “douchebag” to June 11, 1982, and an exchange between actors Henry Thomas, C. Thomas Howell, and Dee Wallace in a little arthouse flick called E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial:

Elliott: But Mom, it was real, I swear!

Tyler: Douchebag, Elliott.

Mary: [swatting Tyler upside the head] No douchebag talk in my house!

BOOM! Box office records indicate that every living man, woman, and child in the United States saw E.T. at least fifteen times—I’m rounding a little—and many of the most enthusiastic and attentive of those repeat viewers were preteen boys. While, true, “douchebag” is not the most memorable insult uttered in the movie, it’s culturally viable in ways that the first-place finisher, “penis-breath,” just ain’t: it’s delivered in a throwaway fashion by a cool older kid (C. Thomas Howell was a child stuntman for the love of god; is that job even legal anymore?) and it also requires a little research to make sense of, and therefore it’s a badge of sophistication. “Penis-breath,” by contrast, is a false friend to its prospective adopter: mannered, idiosyncratic, broadly-delivered by the awkward, earnest, deeply uncool young Elliott, it’s far too easily-sourced to earn its user any locker-room cred.

If you’re willing to entertain my conjecture about the military repurposing of “douchebag” as an anti-hippie slur, then it’s worth putting its cameo in E.T. into some sociopolitical context. If we dust off a useful Slavoj Žižek axiom that I’ve cited in the past—“the first key to horror films is to say: let’s imagine the same story, but without the horror element” (and, okay, sure, E.T.’s not a horror film . . . but it almost was)—then what we have here is a story about a lonely kid and his traumatized family as they try to get over the breakup of a marriage: Dad has skipped town in the company of a new girlfriend, and Mom, suffice to say, is not powering through like a champ. As A. O. Scott (among others) has pointed out, the suburban milieu of E.T. is a grim, lonely, anxious place, due at least in part to the failure of the movie’s baby-boomer parents to assume their proper authority and responsibility and act like grownups for once in their freaking lives. The father—less Peter Pan, we suspect, than Dorian Gray—is totally absent from the film, down in Mexico partying like it’s 1968; meanwhile Elliott’s stunned and frazzled mother treats her kids more like college roommates than legal dependents. It’s pretty clear that teenage boys like to hang around her house because they’ve got the run of the place: nobody’s laying down any law. Their casual use of “douchebag” signals their disdain for the entitled and ineffectual flower-power generation that spawned them but can’t quite manage to rear them, that can’t even keep its own affairs in order.

E.T. can easily—all too easily—be read as a paean to the restorative powers of imaginative fantasy, but it’s important to note that by implication it also advocates for a deux ex machina assertion of cryptofascist control. I mean, c’mon: it is, after all, a shadowy band of all-but-faceless bunny-suited government scientists that swoops in in the third act to legitimate the family’s close encounter and reestablish (or maybe just establish) social order by imposing proto-X-Files martial/exobiological law. The sympathetic researcher played by Peter Coyote is depicted as Elliott all grown up, his sense of enchantment preserved—but he also and more obviously represents the occult knowledge and limitless power of a reinvigorated nation-state. The film’s virtuous abjuration of individual civil liberties and multicultural messiness—paired with its mystificatory and frankly kind of creepy simultaneous embrace of childlike wonderment and skunkworks technocracy—make it a dead solid perfect fable for the Reagan era.

So that, my friends, is the story of First Great Douchebag Breakthrough. By the turn of the next decade, for all kinds of reasons, the word had gathered dust again: incautious overuse had blurred and blunted its impact, new media technologies had made R-rated alternatives more widely available and accepted, and kids had just flat outgrown it. Meanwhile, throughout the land, the cultural circumstances that had made it operative in the first place had shifted, with rising yuppies definitively shunting aging hippies toward irrelevance. “Douchebag” found itself buried deep in the pop-lexical humus where, not surprisingly, it began to mutate once again.

At this point we need not continue to ramble forth without a guide; we can refer to Robert Moor’s essay “On Douchebags,” which appeared in Wag’s Revue in 2009 and was later revised, abbreviated, and reprinted in the n+1 anthology What Was the Hipster?, which is where I first came across it. Moor charts the abrupt rebirth of “douchebag” around the turn of the present century, when it woke from its slumber in answer to a need to name “a certain kind of man—gelled hair, fitted baseball cap, multiple pastel polo shirts with popped collars layered one atop another—who is stereotypically thought to have originated in or around New Jersey, but who, sometime around 2002, suddenly began popping up everywhere (perhaps not coincidentally) just as the nation became familiar with the notion of ‘metrosexuality.’”

This new referent, however, didn’t stick: as Moor points out, “few slang-savvy people today would describe a douchebag as a greasy, Italianate, overtanned, testosterone-rich gym rat.” The early-Aughts connotation of the term seemed to suffer an affliction opposite that of its late-’80s forebear: its meaning was too targeted, because the word was just too good—too potent, too much fun to say—to shackle to such infrequent use. Plus, of course, its rehabilitators no doubt recalled with fondness those middle-school-cafeteria days of yore when no verbal exchange went unadorned by the two-note leitmotif of douchebag; clearly greater semantic ambition was warranted.

Which brings us to the present. What does “douchebag” mean today? This, I suspect, is one of those rare but increasingly common situations when we’re just not going to do any better than Wikipedia:

The term usually refers to a person, usually male, with a variety of negative qualities, specifically arrogance and engaging in obnoxious and/or irritating actions, most often without malicious intent.

Typically wrongfooted too-many-cooks Wikipedia syntax aside, I think this is actually pretty good. The entire post-WWII history of the term fits under the umbrella, from the self-absorbed sanctimony of the hippies, to a broad and irregular litany of 1980s gaucherie (recall that Elliott gets called a douchebag not for claiming to have seen an alien but for ratting out the older kids), to the noxious narcissism of preening millennial meatheads, and more besides. Certain fundamental elements unify all these targets: excessive self-regard, paired with a cluelessness that manifests as incapacity to properly account for the subjectivity of others. The key word in the previous sentence is properly; it’s not that douchebags don’t care what other people think of them—they care a lot—it’s that they overestimate their ability to charm, with confidence based not on sympathetic intuition, nor even on perceptive analysis, but on received technique. A middle-class kid who asserts his participation in the discourse community of the urban lumpenproletariat based on his attentive listening to Chief Keef raps is a douchebag. A dude who professes understanding of ostensibly peculiarly female psychology based on his attentive reading of Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus is a douchebag. And so forth.

I’m sure there’s no shortage of candidates—from Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt to, um, Chief Keef, actually—but based on its sustained focus, the pungency of its indictment, and the historical circumstances in which it emerged, my avant-la-lettre pick for the Greatest American Pop-Cultural Douchebag Case Study of All Time is “Ballad of a Thin Man” from Bob Dylan’s 1965 album Highway 61 Revisited. The song represents an early attempt to pin down a phenomenon in order to better resist it: to point out that a particular number of bothersome individuals can be defined as a type, and that doing so can allow complaints against them to register not (or not just) as petulant sneers but (also) as assertions of competing values.

You’ve been with the professors

And they’ve all liked your looks

With great lawyers you have

Discussed lepers and crooks

You’ve been through all of

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books

You’re very well read

It’s well knownBut something is happening here

And you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mister Jones?

The type of person that Dylan calls out in “Thin Man” was hardly a new feature on the cultural landscape back in ’65. These folks had been around for years, unnamed, rendered invisible by their ubiquity, their social positions fortified by that invisibility. What was new was the type of person that Dylan was: the harbinger and chief prophet of the coming late-’60s counterculture, and of every counterculture that has followed.

This is significant, because the lightning-bolt insight that Robert Moor uses to crack the douchebag code—an insight that doesn’t resist but instead incorporates the term’s propensity to shapeshift—is basically this: a douchebag is the opposite of a hipster. Slick, eh? In exactly the same way that the hipster seeks to stand apart, the douchebag seeks to fit in; in exactly the same way that the hipster seeks to resist hegemonically-imposed common culture, the douchebag seeks to internalize and master it. As Moor puts it (this is from the Wag’s Revue version of the essay):

The douchebag, above all else, seeks a kind of internal legibility, or in simpler terms, normalcy. [. . .] If you listen to his judgments of others, the douchebag reveals that, above all else, he strives just to be normal, to not be “weird”; in fact, to not be labeled at all. [. . .] He yearns more than anything for a stable, non-shifting center, where he can comfortably reside without receiving derision or ridicule. When he succeeds in this task, he is free of stigma, not invisible so much as omnipresent. For that moment he is structurally centralized, an ever-widening nucleus, invisible to himself but projected everywhere he looks.

Let’s look a little closer at the “stable, non-shifting center” that Moor references. To be clear, the douchebag does not achieve this stability and centering the same way that your yoga instructor does: i.e. through reflection and self-assessment, sorting priorities from distractions, articulating and asserting core values, etc. Instead, the douchebag surveys the social landscape, calculates the exact middle of it, and moves toward those coordinates as expeditiously as possible. The idea of assessing his own values and proclivities not only doesn’t enter into this process, but actually produces bafflement in the douchebag, who defines “character” as the extent to which one’s personal habits revert to the norm. The douchebag maintains a suspicion of interiority—his own, and that of others—that borders on revulsion.

One of the cool things about Moor’s analysis is that it posits an interdependent structural relationship between the douchebag and the hipster that’s basically unaffected by the historical specifics of style and fashion; he does a good job depicting the eternal circuit that these two opposed camps are forced to run, as signifiers of hipster quirkiness filter to the mainstream to become signifiers of douchebaggery. Thus neither the douchebag’s stable center nor the hipster’s frontier outpost can ever really exist; both remain perpetually moving targets.

The hipster’s attempts to avoid recuperation by the mainstream—which are motivated by her resistance to having her tastes dictated, and which therefore constitute an assertion of her selfhood—are generally caricatured as flustered and frenetic, accompanied by rolling eyes and furrowing brows. Skinny jeans now fill the racks at Target! Every ex-sorority sales rep now sports a facial piercing and a tattoo! Grrrr, says the stereotypical hipster.

The douchebag, by contrast, is blissful and confident in his conviction that his selfhood can always be assumed, and therefore need never be asserted or examined. Above all else he believes himself to be good at smoothing over potential sites of friction by “saying the right thing,” which amounts to telling people what they want to hear. He regards this not as a symptom of moral weakness but as a skill to take pride in. If this behavior causes him to contradict himself, he’s only fleetingly aware of the contradictions, and anyway doesn’t see what the big deal is. Because of the instinctive rejection of interiority that I mentioned above, accusations of insincerity just don’t mean anything to him: he thinks of himself as a nice guy—respectful and respected, good at his job, whatever it is—who knows how to get along with people. Well, with normal people, anyway. Some weirdoes, y’know, you just can’t do anything with.

Here’s Moor again, this time from the n+1 version of the essay:

The famous douchebag arrogance comes with the false assumption that normalcy has been achieved and that it’s a true triumph. The douchebag who considers himself “relatively normal” thinks he is speaking from a centralized location, a place of authority. To the outside observer, however, he simply looks mediocre and smug. And indeed, why should the douchebag be humble? He is at the center and apex of all things. The average American douchebag is a model citizen of our society: masculine, unaffected, well-rounded, concerned with his physical health, moral (but not puritanical or prude), virile without being sleazy, funny without being clever or snide; he is at all times a faithful consumer, an eager participant, and a contributor to society.

Is this, like, ringing any bells with anybody?

To a great extent, every presidential election since at least 1960 has been a coolness contest, with the cooler major-party candidate consistently prevailing. (I know what you’re thinking, but I am not wrong about this.) This year’s contest, however, seems to break along the hipster/douchebag divide with particular clarity. Sure, you’d have to stretch the definition of “hipster” to fit it around Barack Obama himself—David Brooks’ coinage “bobo” is probably a little closer to the mark (bobos : hipsters : : yuppies : hippies, I suppose)—but I think it’s interesting how the rhetoric of the two candidates and their supporters has recapitulated Moor’s eternal circuit of shifting signifiers: Romney is now freely using Obama’s 2008 conceptual frames, while Obama’s 2012 slogans evoke (as surely they must, given the circumstances) the hipsters’ restless movement toward the next new thing.

At this point, our analysis having reduced American politics to a vacuous fashion system, we might smirk sarcastically and conclude (not entirely without justification) that all the noise associated with the 2012 presidential election has at no point achieved the status of a substantive debate about the nation’s troubled circumstances, and has instead amounted to a pointless and protracted assault on our attention and our dignity: two entrenched constellations of lifestyle enclaves singing traditional fight songs and hurling customary insults at one another. We could conclude that the whole of American civic life adds up to a compulsive reiteration of the social dynamics of a high-school cafeteria, with every clique defined exclusively by its relationship to other cliques in a fixed hierarchy and otherwise devoid of significance or content.

All of that may indeed be the case. Even so, it’s an approximately opposite conclusion that I’d like try to advance here.

As tawdry, stupid, petty, and degrading as our public discourse undoubtedly is—on both sides, and in every direction—there are real stakes on the table: we’re going to be living in a significantly different country four years from now depending on how Tuesday plays out. (And you are hearing this from a guy who unapologetically voted for Ralph Nader in 2000. Calm down; I was in Texas.) While I do believe that most of us decide our affiliations (political and otherwise) at a visceral, emotional, preconscious level and then rationalize them with evidence and analysis after the fact—and I also think it’s clear that some big dollars get spent in efforts to appeal directly to those preconscious attitudes in order to influence our behavior in all kinds of benign and sinister ways—I do NOT think it naturally follows that we should mistrust or reject our visceral reactions. Instead, we should examine those reactions and try to figure out how we came by them, what emotions animate them, and what principles they endorse. My point, in a nutshell, is this: calling Mitt Romney a douchebag is not—or, okay, is not just—a coarse ad hominem attack. It’s also a legitimate articulation of opposing values.

Calling Mitt Romney a douchebag is, for instance, a way of saying that he displays a cavalier disregard for facts. This is not the same thing as calling him a liar; to my way of thinking, in the context of a presidential election, it’s actually worse: liars respect facts enough to know when they’ve parted company with them. Pretty much all candidates for national office lie, in an elbow-throwing, hard-checking, if-you-ain’t-cheatin’-you-ain’t-tryin’ sort of way: Obama and his team certainly cherry-pick statements to paint him in a better and Romney in a worse light, but as lame as this practice is, it really just amounts to spin. Romney’s inconsistencies and factual detours are of a very different order—the kinds of things that make you think surely dude knows people are going to check him on this before you realize that he doesn’t care if anybody checks him.

The highlight reel so far—painfully familiar, but still worthy of review—includes the following: Romney wouldn’t cut taxes for the wealthy; his tax plan wouldn’t add to the deficit; he would maintain full funding for Pell Grants and FEMA, allow no restrictions on insurance coverage for contraception, and keep in place the most popular benefits conveyed by the Affordable Care Act; aside from forcing Chrysler into the Little-Red-Book-fondling hands of the Italians, the federal bailout of the auto industry was implemented exactly as he recommended; he doesn’t favor the strict enforcement of current immigration laws; the stimulus didn’t work; Obama made an “apology tour” of the Middle East after he took office; these are not the droids we’re looking for; and so forth. Every bit of this is either demonstrably factually untrue or has been directly contradicted by the candidate himself.

Romney’s tendency to just make stuff up has a number of troubling implications, but the most obvious one is this: despite the famous contrary assertion by Republican strategists (which I seem hell-bent on referencing in every post: check!), the President of the United States does not get to pick the reality that he or she governs in. Candidates like Romney, for whom candidacy is a full-time job, incur little risk by treating facts with contempt: they occupy no elected office and therefore have none to lose, and if they win they can defend against attempts to hold them to statements they made during the campaign by citing occasions when they stated the exact opposite. But presidents need facts to do their jobs; indeed, the job largely consists of weighing the quality and value of available information to determine a course of action. The terrorist is either in the compound or he’s not; the rogue state will either negotiate or it won’t; the bill either has the votes to pass or it doesn’t. The American electorate has a reasonable expectation of being told how a particular candidate will respond within the bounds of possibility to real conditions once he or she has taken office; Romney’s refusal to do so—or to acknowledge why people might care—is a total douchebag move.

But that ain’t the half of it, kids. Calling Mitt Romney a douchebag is also, critically, a way of saying that there’s just no there there with this guy.

And this is a really big problem. For a long time now (I can refer you to Mark Fisher for some interesting assertions as to just how long) political rhetoric in Western democracies has been unable to support a serious dialogue regarding just about anything of real consequence: it can acknowledge, to a limited extent, the many impending disasters that the world now faces, but realistic suggestions as to how these problems might be solved cannot be posited without being instantly dismissed as “politically impossible.” Examples of these unspeakable subjects include aggressive regulation to limit carbon emissions, the implementation of a national single-payer healthcare plan, across-the-board tax increases at every income level to shore up entitlement programs and pay down the national debt, honestly confronting the ugly legacy of the United States’ conduct in developing nations during the Cold War, creating disincentives to the speculative trade in financial instruments, setting constitutional limitations on campaign financing and the rights of corporate entities . . . you get the picture. All of these topics are “unrealistic,” which is unfortunate because they’re also absolutely necessary: very likely the only approaches that stand a chance in hell of effectively forestalling various looming catastrophes. Anybody with any genuine desire to see these problems addressed ought to be working to enable a public discourse in which these options can be put on the table and evaluated on their merits. There are worse places to begin the project of rehabilitating public discourse than making sure Mitt Romney is not only defeated but discredited on Tuesday, called out for his irresponsible rhetoric on the national stage.

Cuz here’s the thing: with disproportionate thanks to Governor Romney, the 2012 presidential election has actually moved us farther from a capacity to talk about serious stuff. Instead of adopting a bunch of transparently insane but laser-beam-consistent positions and refusing to budge from them—i.e. the Tea Party approach—Romney has declined to take a steady position on much of anything. This is an even bigger deal than the contempt for facts mentioned above: it engenders the absurd spectacle of an enormously expensive and closely-fought presidential election that’s almost completely devoid of politics.

I’m going to say that again: since the conventions, there have been almost no politics discernible in Romney’s campaign. This is not a good thing. Although there are obvious ideological and policy differences between the two major parties, and there’s no question that Romney and Obama would govern very differently, we’ve increasingly had to infer those differences from behind Romney’s ecumenical general-election smokescreen. The public statements that Romney has made in the very recent past (this was particularly apparent in the final debate) have conveyed a consistent message, which is that Romney plans to pursue the Obama administration’s aims using the Obama administration’s methods, but to do so more effectively than Obama has. If we limit ourselves to the public declarations issuing from the candidate’s own mouth—which is not possible since, as mentioned previously, they are almost always at variance with the facts, or with his own earlier statements, or both—then we are forced to conclude that Romney will differ from Obama in his extension of Bush-era tax cuts for the very wealthy, his readiness to privatize Medicare, and his belief that certain federal initiatives should be implemented by the states but remain otherwise unchanged. That’s pretty much it. Romney’s refusal to own and inhabit any single policy position for much longer than it takes him to draw his next breath is not only frustrating but also damaging, in that it further erodes the rhetoric available to all of us to argue productively about much of anything.

This is also pure, classic, peerless douchebag behavior. I really don’t believe that Romney intends to be deceptive; he just doesn’t see any value in wandering in the ideological weeds when that isn’t what—at least to him—this election is about. “I can get this country on track again,” he said during his closing argument in the second debate. “We don’t have to settle for what we’re going through.” He decorated these two sentences with a catalogue of not-too-specific promises of what he’d accomplish as president, none of which was escorted by an explanation of how he’d achieve it, all of which are also identifiable as goals of the Obama administration.

There’s a telling quote from one of the aides on Romney’s 2002 Massachusetts gubernatorial campaign in a recent New Yorker piece by Nicholas Lehmann: “Mitt Romney believes in his competence as a manager,” the aide says. “If he’s elected, he’ll do an adequate job of dealing with the issues of the day. He’s not a vision guy. He’s not policy-driven. He thinks he’ll do a good job.” Romney’s sales pitch to the electorate is simply that he’ll be a better president than Barack Obama has been. Dyed-in-the-wool douchebag that he is, he believes this to be utterly self-evident, almost not worth articulating. He honestly doesn’t understand why anybody would need to know exactly what his values are, given that he’s already spelled out his qualifications. He’s absolutely confident in his ability to turn the country around, and he expects people to share his confidence.

Well, he expects 53% of people to share it, anyway. Some weirdoes you just can’t do anything with.

The defining words of Romney’s 2012 campaign—the infamous remarks surreptitiously recorded at a Boca Raton fundraiser—provide abundant evidence of his willingness to tell different stories to different audiences. This incident was initially assessed as damning because it was thought to show Romney’s true colors on display while safely surrounded by other members of his class; I disagree with that interpretation. I think what we hear in the Boca Raton video is a candidate whose comfort level is conspicuously inversely proportional to the number of people he thinks can hear him talking.

In his initial attempt at overdubbing these comments, Romney described them as “not eloquently stated.” The trouble with that characterization is that he’s more eloquent in the Boca Raton video than he’s been at any other point in the campaign: cogent, candid, forceful, decisive, at ease, in his element. By “in his element” I don’t just mean that he’s hanging out with other super-rich folks, but rather that he’s among people with whom he feels he has a business relationship—his investors, more or less—and for whom he’s in the midst of conducting an analysis. This is how I’m going to get the deal done, he’s saying. This is why it’s worth fifty grand to have dinner with me. He sounds kind of great, frankly. I listen to these remarks and I think: damn, this guy should be in charge of something—something other than the executive branch of the federal government.

The problem with the popular caricature of Mitt Romney as Mr. Moneybags Businessman is not that it’s inaccurate, but that it’s imprecise. There’s capitalists and there’s capitalists, and Romney has been a capitalist of a very particular sort: not an entrepreneur, or a CEO, or even a hedge fund manager, but a private-equity guy. Lehmann’s smart and evenhanded New Yorker piece is really strong on Romney’s experience at Bain Capital, and on what that experience suggests about the way the candidate understands leadership and governance: